My Craving for Domesticated STEM Knowledge

Aug 10, 2025

Abstract

In this entry, I try to put into words why I’ve recently been attracted to a more elemental, organized discipline of science—mathematics. I emphasize the problems I face as an undergraduate researcher in computer science, the tasks I find most interesting, the ones I find most annoying and repetitive, and my goals and motivations for pursuing a bachelor’s degree in mathematics.

Preface

As I stated on the research entry of my homepage, I have always been a STEM-oriented student. My curiosity toward technology (if we can even define what that is) sparked when I was really young. As subjects got harder in middle school, my motivation faded, because our education system is fantastic at teaching students how to solve equations but not very effective at keeping them motivated and engaged. I then became distracted with other teenage stuff—which is as important as studying and taught me useful skills—but this entry is not meant to tackle that topic.

My first academic crash came when I started a B.Sc. in Physics at the University of Salamanca. Much of what happened that year will stay with me for life, but my point is that I became scared of science. Not only because it was traumatic to work so hard to be admitted and then fail many courses, but also because, after I stopped studying at the end of the year (there was nothing to salvage), I had a lot of time to think about my motives. Up to that point, the pursuit of excellence and academic routine had defined me. Without them, I didn’t really know what to do. I crawled back to my family for support and decided to learn a skill I seemed to have missed throughout my adolescence: listening to my parents.

My father, drawing on his research field and years of expertise, recommended that I enroll in a new Bioinformatics B.Sc. at the University of Málaga, called Healthcare Engineering. I listened, and that’s how I got here. I don’t regret enrolling in this degree; I don’t punish myself for it. At the time, neither my father nor I understood how the university science world works as I do now. I’ve put in a lot of work to get where I am, and I’ve accomplished many important things despite the limited “resources” I had available. However, lately I’ve been fantasizing about a more domesticated approach to science—one that doesn’t rely on model comparisons for publication or solely on training and validating black-box functions; a more orderly, yet still functional, science.

Research in Artificial Intelligence (so far)

Artificial intelligence has been the hot topic since the release of ChatGPT when I was in my second undergraduate year. I remember trying to use it to solve a simple “brightest-spot” problem, where we had to find the highest-value pixel within an image from any starting point and within a time limit. It failed to accomplish the task. Now, ChatGPT-5 has just been released, and Sam Altman thinks we are closer to “superintelligence,” even though we don’t really have a clue what intelligence is or how to measure it (apart from the old-fashioned IQ test from the 1910s [1]). Despite the field’s appeal, most of the research conducted in it seems to get lost in the massive ocean of published articles. I can say without doubt that humanity has never produced as much scientific knowledge as it does now, which is not necessarily a bad thing, but it is overwhelming.

As far as I can tell, this is rooted in the “publish or perish” [3] culture in academia, which forces young researchers to produce low-quality papers and choose research topics based on the latest articles in their target journals rather than on curiosity or usefulness.

This fast-producing, fast-publishing academic world made me wonder whether I wanted to spend my early research years as a cog in the machine, or whether I could escape it somehow. I don’t think I can avoid being part of this trend, whether I end up doing research in a computer science department, a mathematics department, or anywhere else. However, extrapolating from Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialist ideas [3], I think it doesn’t really matter whether you’re part of the machine; what matters is whether you have the power to give it your own, subjective meaning.

Looking for Meaning

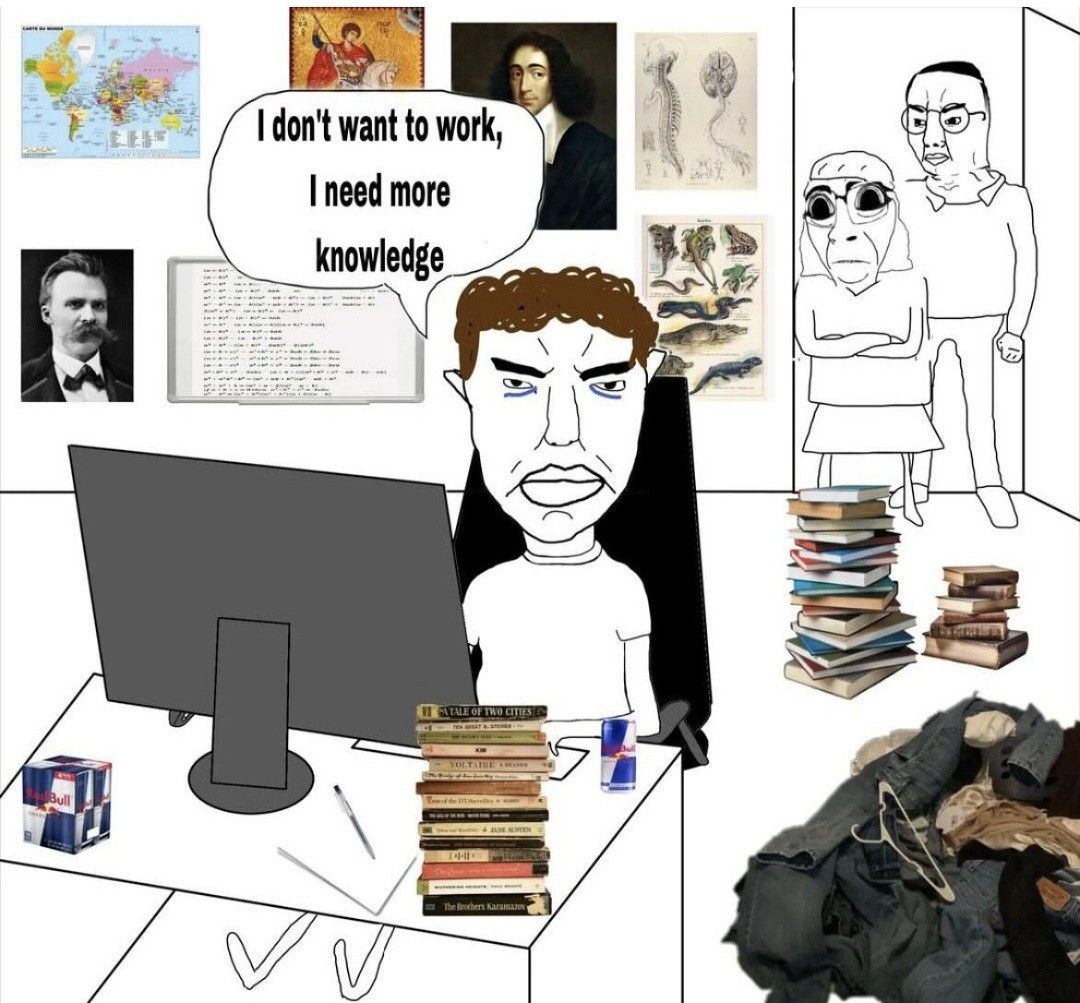

I’ve always had a big flaw: when I’m learning a concept, my mind urges me to understand everything related to it. This became a serious drawback when I started the Physics B.Sc., since I tended to lose a lot of time looking for foundational proofs or underlying phenomena, or experimenting with more basic topics, before moving on with the course material. I learned that it is impossible to understand everything and encapsulate all human knowledge in my brain. Now I feel I have overcorrected for this tendency and entered a loop: find an AI model, adapt my dataset to it, train, validate, compare, report differences, repeat. I feel that college assignments, reviewers’ comments, and simply maintaining my flesh prison consume all the time I might otherwise use to really delve into a topic and understand it, and I’m forced to stay on that endless routine to publish a paper or get the best score in an assignment. And with the next generation of AI models, this pipeline will be covered end-to-end without a doubt.

I’m craving a more domesticated kind of knowledge in my STEM field—one where I can really sit back and spend 5–6 years learning the math, how to prove, how to design with logic in mind, how to understand things from first principles—even if my research slows down, and I may be “too late” for the revolution we’re living through right now. It’s true that I don’t regret choosing this degree, but if I had the opportunity to go back in time (while keeping my current self), I would have chosen a Mathematics B.Sc. (and many other things).

I don’t spend my life punishing myself for my decisions; rather, I take every chance I get to delve into a topic and spend time on myself, my curiosity, and gaining more knowledge, which is what really keeps my mind going (that—and unconditional love from another human being, to be honest). Being a cog in the machine would only have meaning for me if I could sit back occasionally and appreciate the ideas behind the equations—how a model really works and why it works. That is, finding the meaning behind the topic rather than using it as a tool for publishing.

Motivation

Ezequiel López-Rubio is my current mentor, and I admire him in every way you can admire a researcher in your field: an excellent track record, brilliant ideas, constant care for his colleagues, and sustained mentoring of undergraduates. Yet his brilliance is buried under mountains of paperwork required to hold a full professorship in computer science. It seems to have almost no effect on him—as if his days had 30 hours. I, however, have known at least one person I would call a “genius,” and I know I am not one; I am driven by curiosity and hard work, and my days do not have 30 hours.

I feel the only way to truly sit back and learn the math I’ve been missing is to enroll in a Mathematics B.Sc. There are many drawbacks, one being that by the time I finished, I might be “too old” for many research grants or to pursue a Ph.D. in the field (4 years for the B.Sc. + 1 year for the M.Sc. + 4–5 years for the Ph.D.—I’d be 32 and might still lack financial independence). Furthermore, I’m also afraid I would lose contact with Ezequiel’s group and forget what it feels like to do research, having to start over.

I don’t think I would mind being a cog in the machine as long as I truly understand what I’m doing. I wouldn’t fall into the “easy publication” routine; instead, I would think mathematically and reach a justified, scientific solution while proposing useful tools for researchers and clinicians.

Final Thoughts

Even though my career in science hasn’t been what you’d call “normal,” I really enjoy what I do, but I can’t accept that this is the entire research paradigm in AI (unless you’re part of a Nobel Prize–winning group at a top-tier university). This is why I want to take my time to earn a bachelor’s degree in Mathematics: to understand the logic behind most models and natural phenomena.

Everything should make sense—at least to me—and, in my opinion, doing “meaningful research” depends entirely on the researcher rather than others. The question I’m really trying to answer, to keep me motivated despite academia’s “publish or perish” pressure, is: What does “meaningful research” mean to me? As long as it makes sense to me, I will stay motivated, engaged, and proud of my work.

For now, my motivations are: (i) understanding what I’m really doing; (ii) scientifically justifying every action taken in a paper (model tweaks, statistical test decisions, etc.); and (iii) having some impact on someone’s career (as a mentoring teacher, by developing a useful diagnostic or research tool, etc.). To progress on that path, I’ll need to sit back and learn the actual foundations of science.

References

[1] Wikipedia contributors. (2025, August 6). Intelligence quotient. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 13:59, August 10, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Intelligence_quotient&oldid=1304581081

[2] Wikipedia contributors. (2025, July 18). Publish or perish. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 14:26, August 10, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Publish_or_perish&oldid=1301212964

[3] Aho, Kevin, “Existentialism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2025 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), URL = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2025/entries/existentialism/.